Welcome, readers, to my second review of my #20BooksofSummer2025 reading challenge. You can read more about the 20 books I picked in my introductory post here, or check out my first review, Death of an Airman, here.

Introduction

For my second #20BooksofSummer2025 book review, I’ll be discussing The Studio Crime by Ianthe Jerrold, another new-to-me author, and her amateur detective, John Christmas, who is inspired by Dorothy L. Sayers’ creation, Lord Peter Wimsey.

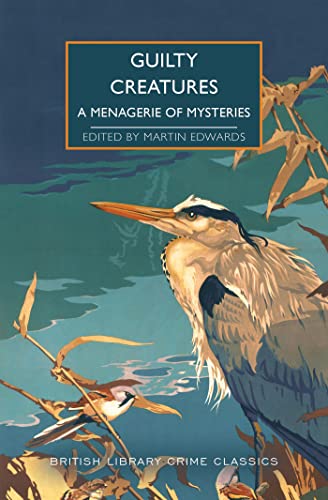

This reprint of The Studio Crime is brought back into readership by Dean Street Press. It includes an insightful introduction by Golden Age Mystery scholar, Curtis Evans, describing Jerrold’s history, contributions to the mystery genre, including being one of the initial members of The Detection Club in 1930.

The Plot

It’s a bad night for most things. But a good night for crime

In The Studio Crime, the readers travel to St. John’s Wood, London, to a party at the home of Lawrence Newtree, a renowned caricaturist. The guests of the party include amateur detective, John Christmas, playwright Serafine Wimpole, and her aunt Imogen, who is devoted to the psychologist, a rather cadaverous Dr. Mordby, the wealthy fiancé and philanthropist Marion Steen, and Dr. Merewether.

As the party unfolds, an unexpected sound emanates from the upstairs apartment of the wealthy art collector, Mr. Frew. Dr. Merewether, sensing unease, ventures upstairs to check on Mr. Frew, whom he had once attended during a long illness. His return, however, brings a shocking revelation-Mr. Frew is fine, but the party is about to take a dramatic turn.

After a brief lull in the party, the guests decide to explore Mr. Frew’s extensive art collection. However, their plans are abruptly halted when their knocks on Mr. Frew’s door go unanswered. After a futile attempt to gain entry, the guests are met with a chilling sight-Mr. Frew, the wealthy art collector, lies lifeless, a victim of a brutal stabbing. Suspicion immediately falls on Dr. Merewether, casting a shadow of doubt over the party.

However, two of the guests mention seeing a strange man in a fez on his way to the studio apartment, possibly to see Frew. Inspector Hembrow and John Christmas are on a manhunt to find the man in the fez and determine who stabbed wealthy Mr. Frew and why.

From almost the start of the investigation, Inspector Hembrow and John Christmas are struck by two truths: Mr. Frew has created a complex artifice to obscure who he is, and that the man called Frew has a streak of cruelty that haunts his friends, enemies, and relations even after his grisly demise.

The Review

On a foggy London night, partygoers sit around discussing how they would commit a murder, while a murder is committed one floor above them. This premise is so strong that it hooked me. The obvious solution to the crime is that Dr. Merewether stabbed Frew, and yet, Dr. Merewether is so kind that it seems too terrible for this man to ruin his life with a murder. Amateur detective John Christmas and I were feeling much along the same line, and so he endeavors to clear Dr. Merewether’s name.

Inspector Hembrow is a more impartial investigator and has no qualms believing Dr. Merewether a murderer. However, upon searching Mr. Frew’s flat, several things become apparant: Mr. Frew was a rather indiscriminate art collector, who had neither taste no skill, he was writing a his memoir, which he believed to be rather incedirary having consulted liable law books, he had a murky past and possible relations he was trying to distance himself from.

Mr. Frew, from the outset, is rather a murky character, who is in sharp contrast to the sharply drawn and wholesome cast of partygoers. Frew employs shifty servants, who will not mourn his death, and is seen as a calculating model. These servants, with their suspicious behavior and lack of mourning, add to the mystery surrounding Frew’s death. Rumors swirl that his bachelorhood is a facade and that he has a wife hidden away somewhere. His business dealings are equally shady, and as the book progresses, blackmail, connections to the drug world, and several other unsavory rumors (and truths) surround the enigma that is the caustic, clever, and cruel man named Mr. Frew. Mr. Frew is such a contrast to the likable Mr. Merewether that it is hard to comprehend how such different men should meet. As John Christmas attempts to clear his friend’s name, he delves into quite a shadowy morass.

One of the main joys of the Studio Crime, besides the central mystery of who the hell is Mr. Frew, is the interplay of the investigative leads. Ianthe Jerrold makes several allusions to Sherlock Holmes, Watson, and Lestrade. However, her trio enjoys poking fun at their literary conterparts. John Christmas is more kindly and follows his intuition more than Holmes ever would, and nervous, shy, introverted Laurence Newtree is world’s away from Watson remarking that he-Newtree-has- has actual work to do and isn’t going to be traipsing around London looking for a random man in a fez.

(However, like Watson follows Holmes, Newtree does traipse around London looking for a man in a fez with Christmas)

Inspector Hembrow is a highly skilled investigator and is incredibly knowledgeable about how crimes are committed on his beat. He remembers long-forgotten crimes and can ferret out the truth from lies. It is easy to imagine that he’s right about how and why a crime happened 99 out a 100 times- but his one flaw- where John Christmas has a slight edge on him in this investigation, is that he doesn’t allow himself to belive in anyone’s innocence based on instinct- they only thing he knows is what the evidence points at and what the evidence points to is Dr. Merewether.

The backstory of Mr. Frew is not as surprising as promised- he is cut from the same cloth as many other men who have wanted to change their future with a new name, and why he is killed is easy to understand- he was a cruel man, but who killed him since he cast his net of vitriol so widely and how was he killed in such a short window.

The Turkish or Greek man in the fez is a tantalizing search, and once he’s found, there’s such a feeling of satisfaction, and yet the reader and John Christmas are left with just enough doubt- is this the man who was outside the studio apartment? He looks like him, yet doesn’t resemble him. To which Newtree queries: what’s the likelihood of two men in fez’s out on a foggy night?

Ianthe Jerrold is exceptional at creating these ‘smoke-and-mirrors moments’, where the reader feels like they understand something about the situation or character before them, and then one small detail doesn’t fit, and the whole thing slips away in a fog of confusion again. These moments of uncertainty and doubt add to the suspense of the narrative, as we, like Hembro, are trying to piece together facts, and somehow the puzzle never quite fits together. John Christmas, however, really studies a man’s soul and in the end can figure out what happened in the studio apartment that foggy night.

John Christmas is a genuinely intriguing investigator —he’s debonair and self-deprecating, and endlessly hilarious in his light ribbing of Newtree. Christmas, also, while disagreeing with Hembrow at nearly every turn, seems to respect his point of view deeply. Ianthe Jerrold makes clear that Christmas isn’t more intelligent than the people around him; just a different type of intelligent one, able to synthesize facts with knowledge of human nature. It’s a shame that John Christmas only features in two books because I think he is a delightful detective.

My Final Thoughts

Ianthe Jerrold wrote an exceptional, character-driven mystery with an enigmatic, villainous victim, several shady possible suspects, and a satisfying ending that brings Frew’s past into the present. The Studio Crime is evocatively atmospheric and features a truly likable investigative trio. Jerrold’s prose, and especially her dialogue, is unnecessarily witty and comical, with numerous darkly comic jabs at the psychiatric profession and literary heroes such as Holmes and Watson. The Studio Crime is an excellent mystery with light, easy prose and a memorable cast of characters. I am looking forward to reading more of Jerrold’s work.

About the Author: Ianthe Jerrold

Ianthe Bridgeman Jerrold (1898–1977) was a British novelist and poet best known for her contributions to the Golden Age of Detective Fiction. Born into a prominent literary family in Kensington, London, she began publishing poetry and short stories in her teens, with early work appearing in The Strand magazine. During World War I, she worked in a munitions factory.

Her first novel, Young Richard Mast, appeared in 1923. She entered the detective genre with The Studio Crime (1929), introducing amateur sleuth John Christmas. Its success earned her a place in the Detection Club alongside Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers. She followed with Dead Man’s Quarry (1930) and later published thrillers like Let Him Lie (1940) and There May Be Danger (1948), the latter republished by Dean Street Press.

Jerrold married George Menges in 1927 and lived in an Elizabethan farmhouse, Cwmmau, which she left to the National Trust upon her death. Her detective fiction has enjoyed renewed interest, securing her reputation as a key figure in early 20th-century British crime writing.

Leave a comment