Laura Dousland, a mysterious young woman, finds herself amid a murder trial, accused of poisoning her elderly husband, Fordish Dousland. The evidence suggests that the poison was administered through a flask of Chianti during supper. With the couple’s Italian servant testifying in court, that the flask vanished on the night of Fordish’s death, the case against Laura Dousland looks black.

However, there is a sliver of doubt when all police efforts to locate the missing Chianti flask are futile. Her defense is that her eccentric husband, who had been mentally unbalanced for years, took the poison of his own accord and hid the flask out of shame.

The verdict of not guilty is reached, and surrounded by staunchly supportive friends, Laura Dousland must cobble together the pieces of her shattered identity and navigate life as a marked woman. Despite the court finding her innocent, she is still a suspicious figure in her small town.

The Cianhti Flask explores what happens after Laura Dousland’s trial, how she heals her fractured identity and strained friendships, and whether it is possible for a notorious woman to ever move on from her past and find love again.

The Review

The Chianti Flask is a book chiefly concerned with what happens after Laura Dousland’s trial. In a Disney movie, it’s the story of what happens after the happily ever after. You know, the part goes straight to home video because it’s just about petty squabbles and home life. But not for Laura Dousland; her ordeal is unfinished, and her dismissal does not absolve her from gossip, suspicion, pity, and benevolent tyranny.

Laura Dousland, a colorless and indecisive woman, was once a governess to a wealthy and benevolent family before her unhappy marriage, which was pseudo-arranged by her employers. When freed, she returns to their bosom. However, she is more resistant to their attempts to mold her into a cheerful and grateful woman, eschewing dinner parties with admirers for her bedroom and refusing to move to Canada to be in the employ of one of their friends.

Laura Dousland, terrorized in her marriage and bulldozed in her employment, stands up to her powerful friends with the aid of Dr. Mark Scutton and goes away to live alone in a secluded cottage by the sea. There, she rediscovers her love of silence, fresh air, good, honest work, and books, and before long, she and Dr. Scutton are in love.

However, she is plagued by requests to sell her story, sell her house, and “go back to her old life” from well-intentioned friends who see her prison ordeal as entertainment.

The readers are invited to watch Laura Dousland heal from her prison sentence, to throw off the bonds of benevolent friendship, who view Laura as a pawn or a possession to be moved based on “what’s best for her” to true friendship, based on her actual personality. We see her nurture true love after a marriage of convenience, which descended into four years of mental and physical abuse.

The Chianti Flask delves into the psychological aspect of healing from traumas, and it does so slowly, tenderly, and honestly. Laura Dousland suffers and backtracks but eventually triumphs over these unhealthy relationships.

However.

Whatever happened to the Chianti flask? If it is ever found, will it prove her innocence or guilt? These questions swirl around the village and around her all the time; she cannot escape them no matter how much she heals, how far she travels, or whether she changes her name.

The last fourth of the book is where the mystery is solved and is anticlimactic. I had worked out a theory that would have made one of the characters very sinister, subtly plotting from the beginning of the book and drawing Laura Dousland subtitling into their clutches and her possibly never even finding out. It was diabolical.

It was also wrong.

The mystery of what happens to the Chianti flask is heavily telegraphed throughout the novel, and the person who hid it is also fairly obvious. There’s no sleight of hand or trickery afoot. The mystery part is probably the least important aspect of the novel by design. The whole thesis of the book is that the author and reasoning behind the crime are unimportant. The crime is born out of pain and not an entertaining puzzle for the reader.

It is a bold position for a mystery book.

Also, it’s boring. I get that’s the point. We, the reader, are supposed to examine “why we love mysteries so much” and “are we any different from the scandalmongers in the book?”

Yes. I contend we are.

This is a fictional mystery, not a true crime TV show or book that we are relishing in. Laura Dousland is not real. I do not owe her the same compassion as I would a flesh-and-blood person. However, moving her healing journey is…it’s not true to life; it’s deeply and utterly romanced.

Mystery novels were more akin to true crime documentaries during this period. I think it’s okay to ask if maybe we relish too much in the pain and suffering of another. If it is akin to watching Bloodsport for entertainment, but the people who populate the Chianti Flask are not real, nor is it based on a true crime, I can revel in the mystery guilt-free.

It’s not much of a mystery; it’s not much of a trial. The Chianti Flask asks us to contemplate what happens to the accused after their justice is meted out. We watch Laura Dousland find her voice, have meaningful friendships, and fall in love with a good man.

When this good man finds out the truth, it alters their relationship utterly, and I am invested. Was she going to lose Mark Scrutton? Was everything just a house of cards that would fall again?

Mark Scrutton and Laura Dousland make their confessions and peace with the past in a few short pages, and the book ends. We don’t get to see their marriage or how the truth colors their married lives, which is a fear repeated ad naseum by Laura Dousland.

Again, this is another bold move.

We, the reader, don’t get the pleasure of being entertained by the wedding or privy to the dilemmas that the truth brings to their marriage. I guess I am to conclude either a) it doesn’t affect their marriage at all or b) that the author’s sole intent is for us to focus on Laura Dousland, the victim of justice.

While I applaud Lowndes’s point of view, it leads her to craft a wholly original type of story. I don’t care about Laura Dousland that much. I don’t care what happens to the victims after they are freed and the trials they face. I read mysteries to escape, be thrilled, and be entertained. I can see the repercussions of a flawed justice system any time I turn on the news,

This book was incredibly thought-provoking for its time, but in the modern era, we contemplate and debate the merits of the legal system in equal measure to the guilt or innocence of a person before the court.

I don’t know if you will like The Chianti Flask; it’s a chimera of a book that I think will greatly appeal to a certain subset of mystery readers but will wholly bore others. If you’ve read this treatise of a post and it sounds appealing, then give it a go. If you want a traditional murder mystery focused on finding a killer, this is not the book for you.

Marie Belloc Lowndes Biography

Marie Belloc Lowndes (1868–1947) was a British author best known for her mystery and suspense novels, particularly her chilling portrayal of psychological tension and social commentary. She was born Marie Adelaide Lowndes on August 5, 1868, in Marylebone, London, England, into a literary family. Her father, Louis Belloc, was a French barrister and journalist, and her brother, Hilaire Belloc, became a prominent writer and poet.

Marie Belloc Lowndes began her writing career in her late twenties, producing short stories and articles for various publications. However, it was her novels that gained her recognition as a talented writer. Her most famous work is “The Lodger” (1913), inspired by the Jack the Ripper murders. This novel, which explores themes of suspicion, paranoia, and the fear of the unknown, has been adapted into several films and stage productions, including Alfred Hitchcock’s 1927 silent film adaptation.

Lowndes’ writing often delved into the darker aspects of human nature, with a particular focus on the psychology of crime and the complexities of interpersonal relationships.

Throughout her career, Lowndes maintained a prolific output, writing novels, short stories, and essays. She also contributed to various literary journals and newspapers. Despite her success as a writer, she lived a relatively private life and little is known about her personal affairs.

Marie Belloc Lowndes passed away on November 14, 1947, leaving behind a legacy of suspenseful and psychologically nuanced fiction that continues to captivate readers today.

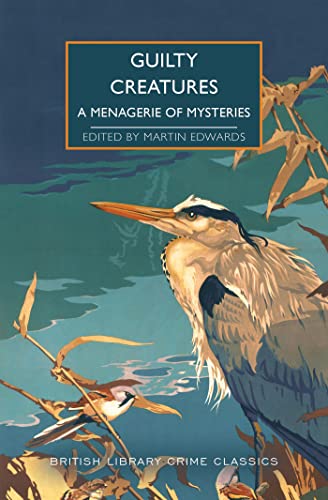

British Library Crime Classics Reviews

The Poisoned Chocolates Case by Anthony Berkeley (1929)

Mystery in the Channel by Freeman Wills Crofts (1931)

The Hog’s Back Mystery by Freeman Wills Crofts (1933)

Murder in the Basement by Anthony Berkeley (1934)

Weekend at Thrackley by Alan Melville (1934)

The Lake District Murder by John Bude (1935)

The Cornish Coast Murder by John Bude (1935)

The Santa Klaus Murder by Mavis Doriel Hay (1936)

Post After Post-Mortem by E.C.R. Lorac (1936)

The Cheltenham Square Murder by John Bude (1937)

These Names Make Clues by E.C.R. Lorac (1937)

Antidote to Venom by Freeman Wills Crofts (1938)

Till Death Do Us Part by John Dickson Carr (1944)

Fell Murder: A Lancashire Murder by E.C.R. Lorac (1944)

Murder by Matchlight by E.C.R. Lorac (1945)

The Theft of the Iron Dogs by E.C.R. Lorac (1946)

Death on the Riviera by John Bude (1952)

Crossed Skis by Carol Carnac (1952)

The Body in the Dumb River by George Bellairs (1961)

Murder by the Book, edited by Martin Edwards (2021)

Leave a comment