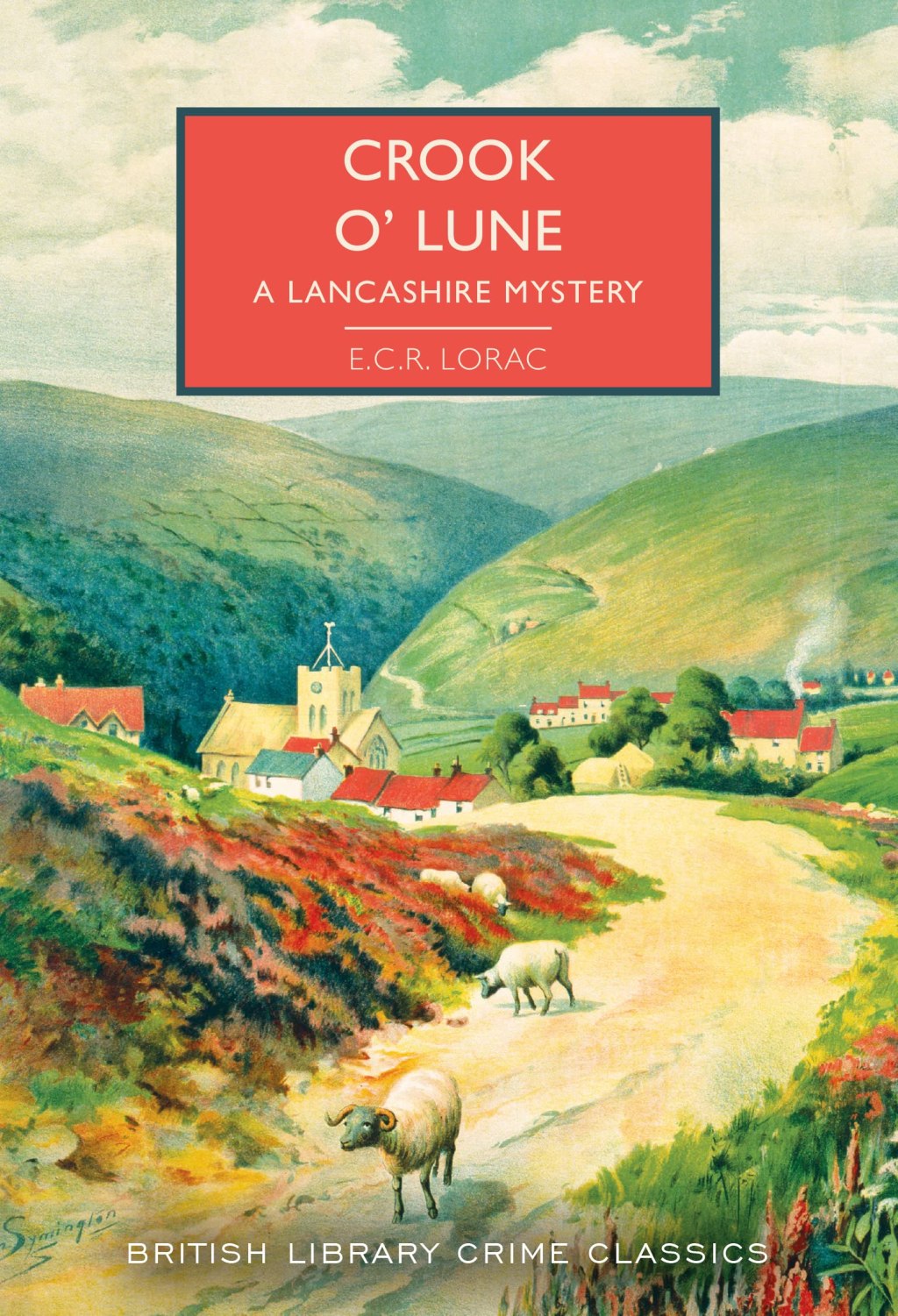

Chief Inspector Macdonald is having a well-deserved holiday in Lunesdale and is visiting his friends Giles and Kate Hoggert at their farm for a few days. While catching up, Macdonald asks their advice on buying a small hobby farm for him to work after he retires from the police in a few years. They are equal parts supportive and skeptical. Farming is hard work and easy to lose money on. However, they promise to take him to a farmstead that will soon go on the market, Aikengill Hall in High Gimmerdale, to see if it is a property he might be interested in buying.

His vacation is cut short by a nasty fire at Aikengill Hall, where the housekeeper is killed in the fire. Rumors swirl in the valley that the fire was set on purpose by two young lovers hoping to rent the upstairs apartment and look after the house when the wealthy new proprietor Gilbert Woolfall was away on business.

Gilbert Woolfall recently inherited Aikengill upon his uncle’s recent passing. The house and his uncle’s historical papers are of immense interest to Woolfall, and he has spent many months running the farm, probating money issues stemming from his uncle’s death, and collating his uncle’s vast historical memoirs of the families and history of the Lune Valley.

Gilbert Woolfall is generally well-liked, but knows he is an outsider and is unable to properly farm the land and keep up his business in the city. Several people offer to buy or look after the property since housing is scarce in the area, but he skillfully evades committing the property to anyone.

His only real enemy is the local parson, who hopes to get Woolfall to endow the local church, the parson, and the local school with a financial bequest. The parson contends that it was once the duty of this wealthy family to supply a large endowment to the church, and Woolfall’s uncle had broken with this long-standing agreement, which was initially made due to land deals because he felt that the money was not being spent wisely. The person argues with Woolfall that as the new owner of Aikengill, it is now his responsibility to renew the old agreement. Woolfall is genial but firm in refusing the parson’s request for financial support and upholds his uncle’s wishes.

When the fire burns half of Aikengill to the ground. Macdonald is originally called in to “consult” on the case since the local police are inexperienced with handling arson deaths. However, Macdonald soon realizes that Woolfall was playing a dangerous game, pitting people’s hopes against each other’s to get his land. Land is scarce and precious in the Lune Valley and buried deep in the history of the valley is the secret for this horrific and brutal murder.

The Review

Crook o’ Lune is a book primarily about the relationship between land and its owners and how this precious resource can lead to complex relationships and contractual obligations. When the Lune Valley was formed, the small homesteads and larger farms created a complex system of partnership and, in later generations, financial commitments, which bleed into creating loyalties and enemies. This web is intricate and often unspoken, keeping the community functioning smoothly.

High Gimmerdale thrives on these invisible, invisible threads that bind, and all is going well until Gilbert Woolfall takes control of Aikengill. The community tolerated his uncle’s break from supporting the church with quiet aggrievance. Still, when his breach of social ethics was to be continued, it set off a chain reaction of literarily explosive consequences.

The Lune Valley is a microcosm of farming life and the fabric that the inhabitants weave to survive. Their way of life, already profoundly disrupted by war, is fighting a losing battle with its younger generations who want to leave the farm for fortune elsewhere. The people who cannot seek a life elsewhere hold fast to tradition. When this kind but meddlesome outsider decides not to right his uncle’s transgression against the community, he stands on shaky ground with his neighbors.

Land is the tie that binds.

Crook o’ Lune, part travelogue, part philosophy, part historical fiction about the rapid decline of the farming communities that make up rural Britain, has much to say about life after World War II in England. It’s beautiful and haunting, burnished with sadness for how the sands of time and the economic tumult of war are unraveling the symbiotic relationships held by Britons for centuries.

This mystery is reflective and moody, slowly unveiling how generations of people and their desire to be their brother’s keeper are the brick and mortar of life in a small, isolated village and how it can easily crumble when people don’t do their share.

Macdonald, loved by many in the community, watches as it devours its own for revenge and atonement. To live in this unspoiled valley and to farm with its hardy inhabitants comes at a steep price. It’s a sobering lesson for Macdonald and obliterates his notions about a “play acting” farmer. You are either one of the people of the valley and live up to the community, or we have no use for you. The land should be taken seriously and not just be a place to wipe away your golden years.

It’s a hard lesson to learn, and I won’t spoil Macdonald’s decision about whether he chooses to settle there.

The mystery, pastoral and at times quite dry—be ready to hear long discursions on church history and family history and meandering paragraphs where most of the meaning is in the pregnant pauses or what is left unsaid—will not appeal to everyone. However, as a person who lives in a small farming community, I think it rings true.

Crook’ o Lune is a book concerned with crimes that only arise out of rural life; it’s about people betraying each other, how land is the most valuable currency, and how people will do anything murder- to get their hands on it.

This book dwells on many poignant themes that likely resonated quite deeply with her audience at the time of publication. They are seeing the old ways of life fade to the gleam and glitter of modernity, where an apartment is more attractive than a large, greedy, backbreaking farm.

It’s fascinating reading Crook o’ Lune today- in the aftermath of the mad rush to cities. Family farming still relies on these same unspoken agreements in the small pockets that still exist. Out where I live, some farms are in their seventh generation, and they live and die on the youngest generation’s commitment to “running the farm.” I also live in an age where all the people who relocated to the city, whose forefathers once owned large, affordable family homes, cannot promise the same to their children. Most of my generation (Millennials) and those behind me know that home ownership- never mind landownership is a hard-won luxury.

Land is the tie that binds, so break the bond carefully.

Crook o’ Lune is a book that gave me much to think about, wrapped in a cozy mystery. However, this book is the most slow-moving and extemporaneous of her Lunesdale subset of Macdonald mysteries. I like them, and they have a lot of poignant ideas, but I miss her earlier works, which are more focused on clever mysteries and puzzles over philosophy.

E.C.R. Lorac Biography

Edith Caroline Rivett, who wrote under the pen names E.C.R. Lorac and Carol Carnac, was a British crime writer born on November 6, 1894, and died on August 2, 1958. She was a prolific author, best known for her detective fiction, particularly her series featuring Chief Inspector Robert Macdonald.

Lorac was born in Hendon, Middlesex, England. She began her writing career in the 1930s and published over 60 novels, most of which were detective stories. Her writing style often featured intricate plots, well-developed characters, and a keen attention to detail.

During her lifetime, Lorac was a respected member of the prestigious Detection Club, an association of British mystery writers founded in 1930 by a group of leading crime writers, including Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers.

Lorac’s novels were set in various locations, including London and the English countryside, and she often drew on her own experiences and observations of British society. Her works were praised for their strong sense of place and atmosphere, as well as their cleverly crafted mysteries.

Despite her prolific output and popularity during her lifetime, Lorac’s works fell out of print for several decades after her death. However, there has been a renewed interest in her writings in recent years, with several of her novels being reissued and republished for a new generation of readers to enjoy.

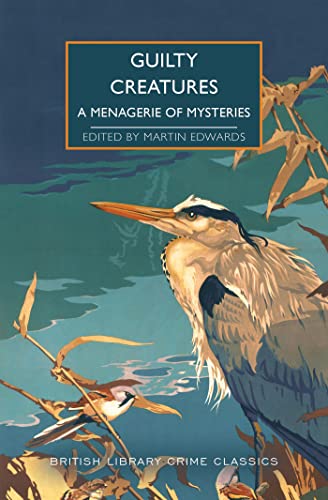

The British Library Crime Classics Reviews

The Poisoned Chocolates Case by Anthony Berkeley (1929)

Mystery in the Channel by Freeman Wills Crofts (1931)

The Hog’s Back Mystery by Freeman Wills Crofts (1933)

Murder in the Basement by Anthony Berkeley (1934)

Weekend at Thrackley by Alan Melville (1934)

The Lake District Murder by John Bude (1935)

The Cornish Coast Murder by John Bude (1935)

The Chianti Flask by Marie Belloc Lowndes

The Santa Klaus Murder by Mavis Doriel Hay (1936)

Post After Post-Mortem by E.C.R. Lorac (1936)

The Cheltenham Square Murder by John Bude (1937)

These Names Make Clues by E.C.R. Lorac (1937)

Antidote to Venom by Freeman Wills Crofts (1938)

Till Death Do Us Part by John Dickson Carr (1944)

Fell Murder: A Lancashire Murder by E.C.R. Lorac (1944)

Murder by Matchlight by E.C.R. Lorac (1945)

The Theft of the Iron Dogs by E.C.R. Lorac (1946)

Death on the Riviera by John Bude (1952)

Crossed Skis by Carol Carnac (1952)

The Body in the Dumb River by George Bellairs (1961)

Murder by the Book, edited by Martin Edwards (2021)

Leave a comment