Hugh Everton, a hotel food and drink critic, spends his dreary days evaluating second-rate establishments in tony seaside towns nobody ever visits. He’s trying to stay on the straight and narrow after being thrown out of the foreign service for passing a fraudulent check three years ago. He served jail and is now trying to commit to a dull, regular life.

However, his resolve is tested when Lucy Bath, his old flame, walks in, for whom he got embroiled in the lousy check scheme in the first place. Hanging off her arm is her latest elderly husband, Judge Gregory Bath. She also has a small entourage of conmen, one of whom Everton recognizes as a man named Ronson, with whom she ran criminal schemes before, although now he calls himself Atkinson.

He tries to keep the conversation with the alluring and deadly Lucy Bath to a minimum and notices things are strained in the little group. He is surprised when Lucy invites him back to her colonial-style mansion on the coast for a night. He accepts, hoping to see his old girlfriend, Lucy’s niece by marriage, and mend their broken relationship.

Everyone in the house is nervy, barely paying attention to their card games and talking in queer riddles. Gregory Bath invites Hugh Everton on a tour of the house, and he seems like he’s about to take Everton into his confidence about whatever weird scheme is being pulled at the house when he ultimately decides to clam up.

Everton goes back to Lucy and her friends when they all hear a shot, and then the dog, who has been missing all day, lets out a blood-curdling howl. Lucy and Atkinson rush upstairs and eventually come down, saying that George Bath has been murdered, and the rest of the guests go upstairs to see the body.

Soon, the police come to investigate, but when they go upstairs to examine the body, it’s gone.

Suicide or murder.

A strange cover-up, blackmailing witnesses, espionage, and criminal activity are among the vices teaming beneath the surface of this tiny seaside resort town.

The Review

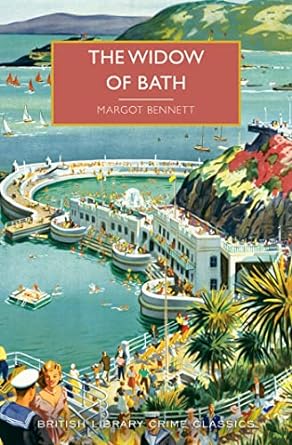

The Widow of Bath is a weird book. Margot Bennett breaks from the usual genteel writing style of a British country house mystery. She tries to interject more hardboiled and noir elements into the story, especially the dialogue, which is at times almost incomprehensible, almost comedic, and very impressionistic.

The hero, Hugh Everton, seems like he’s trying to be ripped from a 1930’s noir mystery, with a more amoral bent. He’s fast-talking, punches faster than he thinks, and is trying to fight off his destiny to have a head-first collision with Lucy Bath. However, there’s something. artificial, and not quite right about these quintessentially American detective story elements. They feel like their written by artificial intelligence.

The real problem is that Margot Bennett doesn’t go far enough with the grit. Her hero is too weak-willed. He’s not a man with a solid moral or personal code that clashes with the harsh world around him. He’s a man who can’t ever say no and, therefore, has to keep fighting his way out of bad decisions. It’s a twist on the anti-hero archetype that grates and exasperates instead of getting the reader on Hugh Everton’s side.

The femme fatale, Lucy Bath, is beautiful but a shade too stupid. The men that paw after her are solely in her wake to gaze upon her beauty, but true femme fatales have brains and usually some cruel power over their minions, which is taken away at the end. The Widow of Bath ensures that the reader knows that Lucy Bath is alluring and that we know she isn’t cunning. Her fake evidence is seen through at once, and she is blackmailed!

All the characters are just a little too comedic and broad to fit into the sharp-edged confines of a noir novel. The same issues affect the seaside town. It’s run down and a little seedy but not dangerous, like New York, Detroit, or Chicago, which often populate noir novels. The pulsing, grinding, amoral, and evil city is so far removed from a seedy seaside town that it’s almost funny.

Margot Bennett is trying to write in a genre that requires a level of malevolence that sucks the spirit out of every good thing that she just won’t commit to, and the character and setting suffer. The reader can tell it’s a world that is unfamiliar and unknown to her.

When Frances Crane tried to write an American-led British country house mystery in The Applegreen Cat, outsiders couldn’t replicate some genres. They fall flat, get all the ingredients, but somehow never come together right.

The mystery is good, if a bit impenetrable. Margot Bennet really likes to present an idea line of inquiry, or even a character’s past in a certain way, even discussed by a character as happening a certain way and then having them change their mind or something happening to recontextualize the narration so the opposite thing is now confirmed.

There’s a feeling of irreality like everything is built on a hill of sand sliding out to sea. I am not sure things happened in the past because Bennett leaves details vague, fuzzy, and ragged. Is Atkinson really Ronson? I don’t know if that is ever definitively established. Did Ronson try to drown Everton, or did Everton try to commit suicide after Lucy rejected him before he went to prison? Everton presents both as facts and maybe both are.

Everton, which is not established in this small town, has to do a lot of mental gymnastics to keep being involved with witnesses and the police. Bennett needed to commit to a reason for Everton being involved or have him admit it was due to several reasons, but she kept it nebulous.

Did Judge Bath commit suicide, was he killed, and who killed him? All of these solutions are true at one point in the story, with Everton backing each horse until someone tells him he’s wrong. His investigative technique is standing around until someone confesses their involvement in the crime.

That’s exactly how the crime is solved. The motive made sense but was also way out in the left field. I liked it. I think the culprit got away with the crime, but maybe they also committed suicide. The ending was a bit extravagant and made me wish it was a movie where the authorial intent was more apparent through framing, music, and other imagery. Maybe I just didn’t “get it.”

Everything is far from the usual tropes, and I liked how I never really knew what was going on until the final twist and confession. Sometimes, these more experimental risks really paid off, and other times, especially with the added espionage subplot, the idea of bringing in war criminals seemed too outlandish to be believed.

The ring of criminals who pose as waiters before being shipped out to new locales with the anonymity of new identities is tipped off way too early. Everton, who isn’t incredibly clever, can see right through them from the beginning but doesn’t connect the apparent dots until the end.

The police are somewhat better; they know about the criminal gang, and they also know that Lucy Bath is involved in the criminal ring and suspect her of having a hand in at least attempting to kill her husband- but do they bring her in and press her about her crimes, no. They let Everton bumble around and are pissed that he keeps fucking up their investigation, but also, they don’t really move forward with the investigation.

They know a girl drowned and cover up what happened to Gregory Bath; they know how she was lured to her death and why she met up with the suspect, and they can narrow down the suspect pool to three. Instead of bringing them in, the police politely ask all of the suspects if they killed the witness. Then, we never see the follow-up because our guide through the book, Hugh Everton, is never aligned with the police or able to get them to confide anything to them.

The characters are so strange and unreal, and the subplots are so disparate that they never gel into a story. There’s a police investigation totally separate from Everton’s bumbling; a love triangle between Everton, Lucy, and his old girlfriend is eventually resolved, but it never really shows the reader why he picked the lady he liked.

Why does anything happen in this book the way it does? I don’t know because Margot Bennett says so, whether it makes a lick of sense or not. This can lead to some excellent twists and a totally original plot. Still, it can also be maddening to grasp character motivations, which can lead to a comprehensible arc.

I honestly don’t know if you’ll like this book. I don’t know if I liked this book!

If you want a more experimental book that takes risks and doesn’t always succeed, then definitely give this quirky mystery a read.

Margot Bennett Biography

Margot Bennett was born on June 6, 1912, in Streatham, South London, England. She grew up in a literary environment, as her father, Arnold Bennett, was a prominent novelist and critic. However, her parents’ marriage was not stable, and this instability deeply affected her childhood.

Despite the challenging family dynamics, Bennett developed a passion for writing from an early age. She attended St. Paul’s Girls’ School in London and later studied at Somerville College, Oxford, where she pursued her interest in literature.

In 1933, Bennett married the economist Kenneth Richmond. The couple had two daughters before their marriage ended in divorce in 1947. During this period, Bennett began her career as a writer, initially focusing on poetry and literary criticism. However, she eventually found her niche in crime fiction, a genre that allowed her to explore complex characters and intricate plots.

Bennett’s writing career flourished in the 1950s and 1960s, during which she published several acclaimed novels, including “The Widow of Bath” (1956), “The Man Who Didn’t Fly” (1968), and “Someone from the Past” (1976). Her works were known for their psychological depth, gripping narratives, and sharp social commentary.

Beyond her career as a novelist, Bennett was actively involved in various literary activities. She served as the chair of the Crime Writers’ Association and was a respected critic, contributing reviews and articles to leading publications.

Despite her literary success, Bennett faced personal challenges, including financial difficulties and health issues. She struggled with depression throughout her life, which at times impacted her productivity as a writer.

Margot Bennett passed away on January 9, 1980, leaving behind a legacy of compelling crime fiction and literary contributions. Though she may not have achieved widespread recognition during her lifetime, her work continues to be appreciated by fans of the genre, and she remains an important figure in British crime fiction history.

British Library Crime Classics Reviews

The Poisoned Chocolates Case by Anthony Berkeley (1929)

Mystery in the Channel by Freeman Wills Crofts (1931)

The Hog’s Back Mystery by Freeman Wills Crofts (1933)

Murder in the Basement by Anthony Berkeley (1934)

Weekend at Thrackley by Alan Melville (1934)

The Chianti Flask by Marie Belloc Lowndes (1935)

The Lake District Murder by John Bude (1935)

The Cornish Coast Murder by John Bude (1935)

Death of an Author by E.C.R. Lorac (1935)

The Santa Klaus Murder by Mavis Doriel Hay (1936)

Murder in Piccadilly by Charles Kingston (1936)

Post After Post-Mortem by E.C.R. Lorac (1936)

The Cheltenham Square Murder by John Bude (1937)

These Names Make Clues by E.C.R. Lorac (1937)

Antidote to Venom by Freeman Wills Crofts (1938)

Till Death Do Us Part by John Dickson Carr (1944)

Fell Murder: A Lancashire Murder by E.C.R. Lorac (1944)

Murder by Matchlight by E.C.R. Lorac (1945)

The Theft of the Iron Dogs by E.C.R. Lorac (1946)

Death Has Deep Roots by Michael Gilbert (1951)

Death on the Riviera by John Bude (1952)

Crossed Skis by Carol Carnac (1952)

Crook o’ Lune by E.C.R. Lorac (1953)

The Body in the Dumb River by George Bellairs (1961)

Murder by the Book, edited by Martin Edwards (2021)

Leave a reply to April 2024 Monthly Wrap-Up – Golden Age of Detective Fiction Cancel reply